Just a short distance from where we are staying in Bloomfield, NM, are the Salmon Ruins built by Ancestral Puebloans between AD 1088-1090. They lived here until 1150 when people began to move east to the Rio Grande valley and were an outlier Chacoan pueblo. The property was homesteaded in 1877 by Peter Milton Salmon and owned by his family until 1957 when it passed to Charles Dustin. In 1969, he sold it to the San Juan County Association so it could be protected from vandalism.

The ruins were excavated between 1972-78 under the direction Dr. Cynthia Irwin-Williams. The San Juan Archaeological Research Center and Library is open to the public.

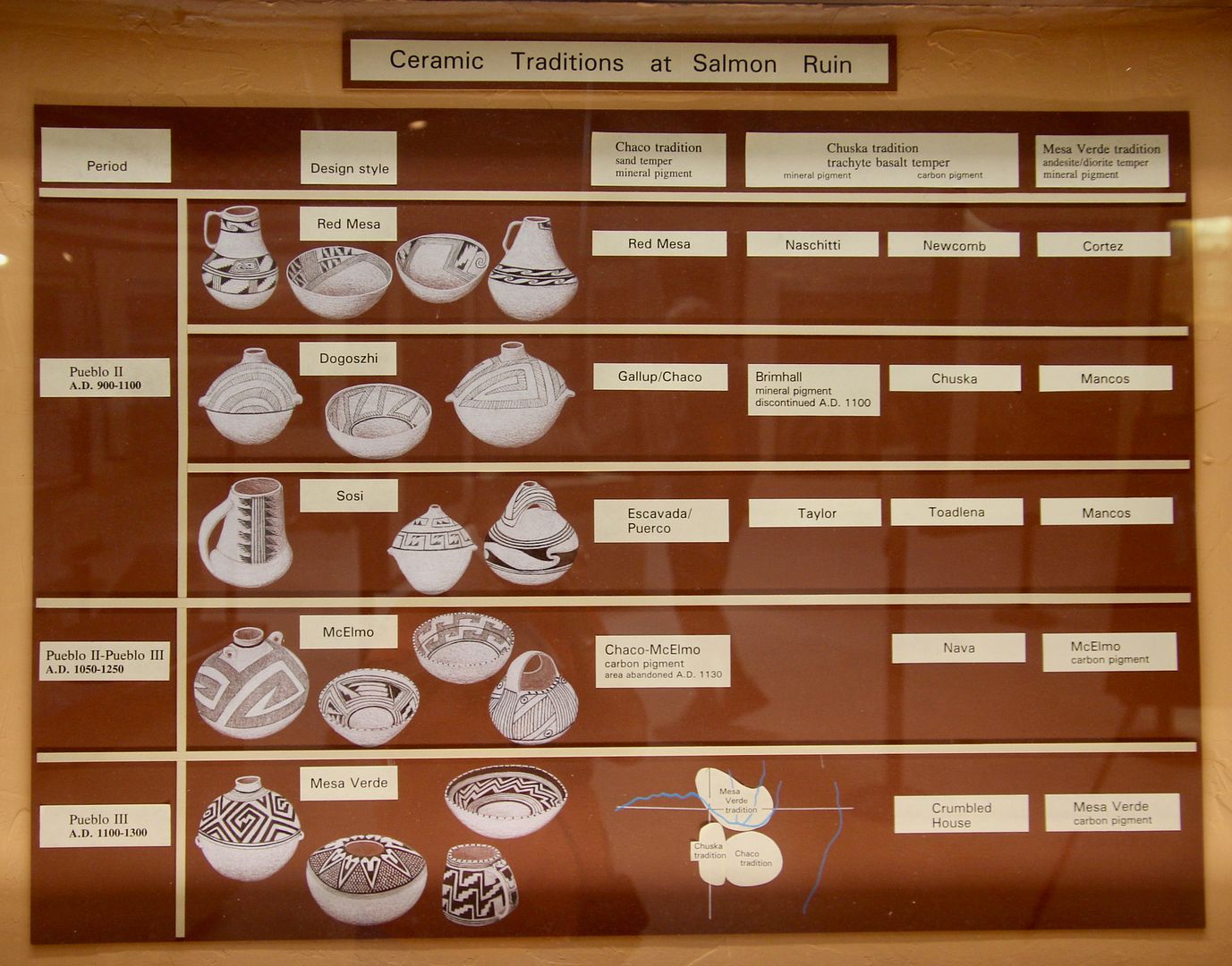

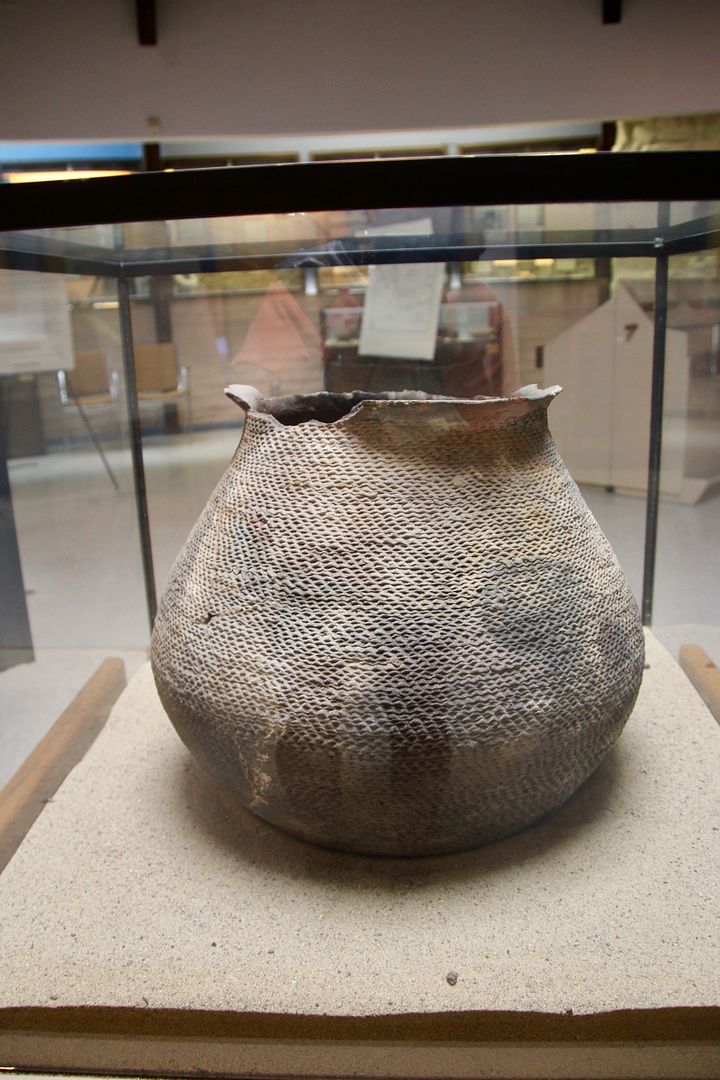

Exhibits about the ceramics, rock art, textiles, rock tools and other artifacts found here can be seen in the museum.

There are two areas (Heritage Park and the Ruins) outside to explore and you can either walk or drive to them (we drove). There is an amphitheater for educational programs at the park.

We walked to the Heritage Park area (pets allowed) where the first building we saw was the 4-room house built by George Salmon in 1898. Unlike the traditional log home built with horizontal logs, this house has vertical and horizontal roof pole construction of juniper and cottonwood trees (which were then covered with juniper bark, mud plaster, and loose dirt).

Heritage Park has replica structures that show the architectural styles and cultures of the region. Each were built using only those methods available corresponding to the time of the original construction. Trading Posts served as intermediaries between the inhabitants of town and the reservations where bartering was the means of the exchange of goods. Here is a reconstructed one that once stood here.

Below is a ramada (temporary structure to provide shade) and sweat lodge used by men. Also shown is a male hogan.

In the canyons that currently make up the Navajo Nation are thousands of rock art panels created by the Navajo. And, some contain even earlier art by Ancestral Puebloans.

The Jicarilla Apache built small temporary brush structures for a single night’s shelter. They planted seeds and then went in search of game and plants to gather (similar to the lifestyle of Plains Indians). The Weeminuche Ute were also similar to the Plains Indians. The Ute trained dogs to pull their travois and followed herds of game animals. They lived in tipis of animal hides sewn together to fit the frame. An open flap meant all visitors welcome; a closed flap meant that a visitor should make a noise or call out prior to entering; and two crossed sticks over the closed door meant “do not disturb.”

Pit houses were huge investments of effort for those that constructed them (AD 200-700). They became more popular as people began to raise crops and live n semi-permanent housing. These types of homes have been found all over the world as they provided a comfortable interior temperature during either hot or cold weather. The earthen bench-like feature around the perimeter was likely used for sleeping.

This is an (incomplete) Ancestral Pueblo of the time period AD 700-900. Eventually, people began building structures above ground instead of the pit houses of earlier times.

The Salmons also built a bunkhouse, corral, root cellar, well and planted fruit trees (some are still here). Irrigation ditches supplied the water for the trees and gardens.

I continued to the remains of the pueblo that once stood here (no pets allowed here). It was originally three stories tall and had approximately 350 rooms. A map (obtained at the museum) provides insight into the construction and uses of the various rooms of the pueblo. The self-guided tour begins at the northeast corner where the wall was 394’ long on one side and the eastern wall was 164’ long.

The ruins reveal the classic Chacoan wall construction with unshaped rocks/mud in the middle with veneer (precisely cut, smooth, flat-facing sandstone) on the exterior of the wall. You can see this same design in all of the Chaco culture structures.

Sandstone blocks used here were quarried about three miles away. And the timbers used to construct multiple floors were procured from forests 25 miles away (and carried by hand to the site). The burial of an infant (estimated at 4-8 months) was found in this long/narrow room. It was not uncommon for Ancestral Puebloans to bury beloved family members in the lower story rooms of a pueblo.

This kiva dates to AD 1190 and originally had a painted band painted dark red with white designs. It had a corbelled roof with stacking logs of diminishing size in a spiral resulting in a dome shape. The center would have been left open with a ladder for access and a vent for the fire. The wood seen here dates to the original construction.

Two macaws and two turkeys were formally buried in this room, providing evidence that there birds were being raised here (for trade) in Mesoamerica. Wow! The second room is a typical living space where food was prepared.

Below are several views from what would have been the second story of the pueblo.

And this is a view from what would have been the third floor. The holes along the wall show where timber was placed to support the second (or third) floor.

The Tower Kiva was the most important room in the Pueblo and is typical of other kivas found in the Chaco Culture. Several smaller kivas can also be seen.

Kudos to the San Juan Archeological Research Center for protecting this historic site. The excavations provided insight into the way of life in this location over a thousand years ago. I find these Ancestral Pueblo sites fascinating and we plan to see many more over the next month.

Admission is $3/seniors; $4/adults. For additional information about Salmon Ruins, go to www.salmonruins.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment