You can obtain information and a brochure that serves as a guide to the walking tour of the site there. Also, a small gift shop and several exhibits are located at the Visitor Center.

The flowers in the gardens surrounding it attracted beautiful butterflies and bees.

History: Mark Bird built the Hopewell Furnace in eastern Pennsylvania (near Birdsboro and Morgantown) in 1771. The blast furnace technology used to produce iron had been brought to the colonies from England in the mid 1600s. By the time the Revolutionary War broke out in 1775, America was producing one seventh of iron products globally.

Economic hardships followed the War and the 1788 Hopewell Plantations was sold at a sheriff's sale but the new owners closed the furnace in 1808. In 1816, Clement Brooke re-opened the furnace and was the on-site manager until 1831. The furnace closed in 1883 for good. The Brooke family maintained summer homes on the property until it was sold to the federal government in 1935.

Process: The process to produce iron remained basically the same for 4,000 years and is what was used at Hopewell Furnace. The three basic ingredients to make iron were: iron ore, limestone (aka flux), and carbon fuel (charcoal), all found in the area.

The iron ore was dug out of small surface mines. The abundant forests of Pennsylvania provided the woodlands needed to produce charcoal (one acre of forest was required to produce enough charcoal to run an iron furnace for just one day). 5,000-6,000 cords of wood were used each year to produce charcoal at Hopewell Furnace. The process was managed by a collier.

Below is a charcoal hearth and a shed for the collier that provided some shelter from the intense heat during the process.

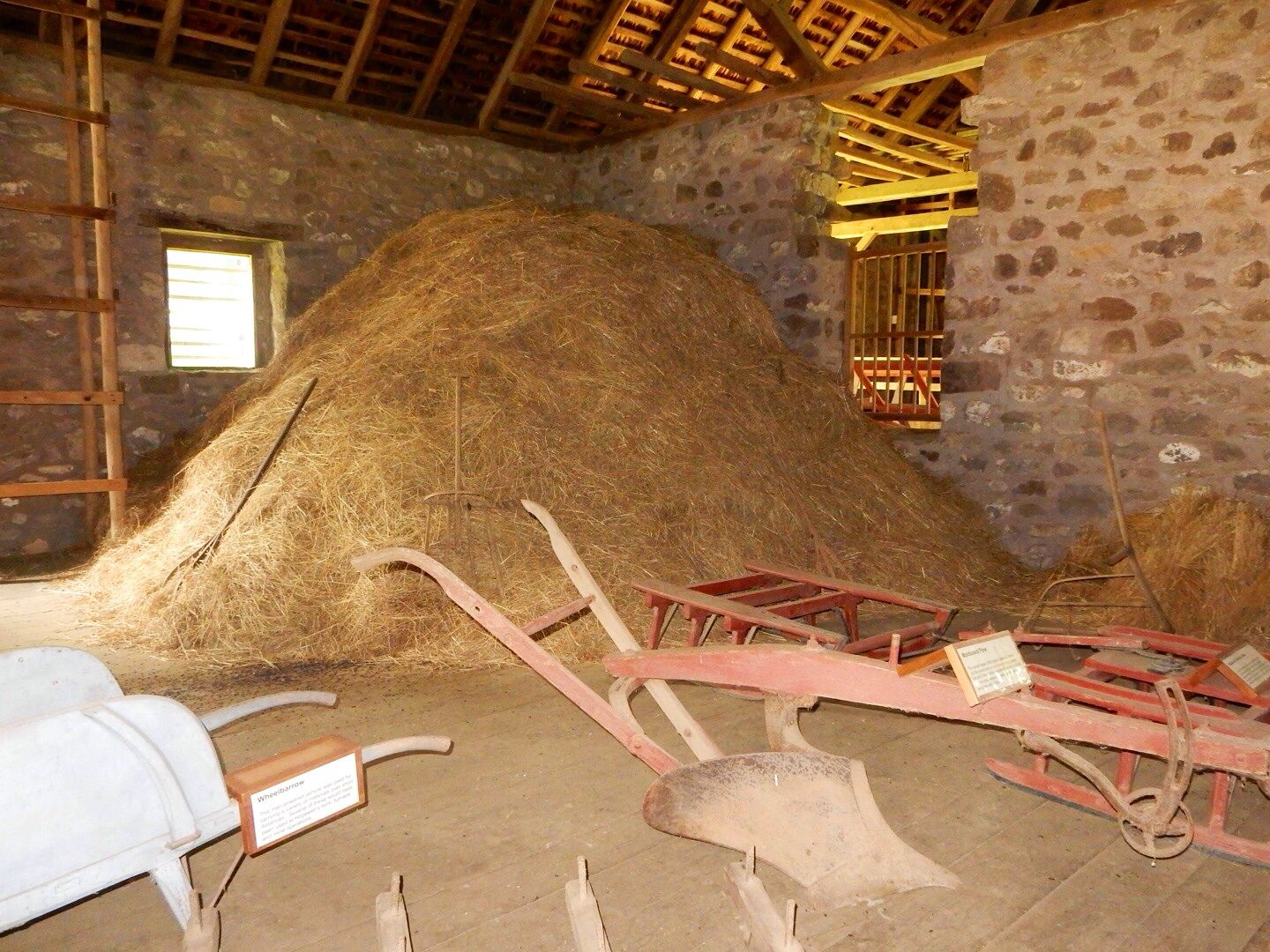

Charcoal was loaded into wagons and taken to the cooling shed by teamsters. Once cooled, the charcoal was moved to the charcoal house.

The final ingredient needed was air that was pushed into the hearth by the water-powered blast machinery. Power was provided by the water wheel. The temperature in the furnace was about 3,000 degrees F.

The office store was available for workers to purchase goods against credits for their work. This is also where workers documented the work they had done each day and where the paymaster was located. Because there were multiple furnaces in the area, the skilled workers could easily get another job elsewhere if they were unhappy with the Hopewell Furnace operation.

There was a basket of shorn wool from one of the sheep raised here. They demonstrate the shearing for the public once a year.

The meal shed was next to the office store. Bulk grain and meal was sold to the Hopewell furnace workers and their families here.

Moulders cast iron into stove plates and other products in the cast house.

Hardware and horseshoes were produced at the blacksmith shop.

Tenant houses were available for rent by workers and their families for $12-$24/year in the late 1700s.

There was also a boarding house for single men, although some workers rented a room from a family in a tenant house. The second photo is the lovely view from the house to the furnace.

Draft animals (up to 36) were sheltered in the barn and at least a year's worth of feed was stored there.

The springhouse and smokehouse were used to cure meats and store food.

The ironmaster's mansion is open for self-guided tours of the first floor. There is an audio recording that can be heard by pressing the button found in the entrance hall that provides some history on the residence. The first home was built c 1775 and was remodeled numerous times with the last one occuring c 1870.

An anthracite furnace was built at Hopewell, but use of this hot-blast technology failed here after four years. The anthracite furnace used coal instead of charcoal. In future years, anthracite furnaces totally replaced charcoal furnaces.

Rural iron making operations have been called "iron plantations." They were self-sufficient communities with craftsman, laborers, agriculture, and families. The ironmaster directed the operations and was often the owner. Second to him was the clerk/helper who kept the records, order supplies, and was responsible for operating the office store. The highest paid works were moulders; they were responsible for casting the iron. The colliers (charcoal makers), miners (for the ore), and woodcutters supplied the materials required to produce the iron. Women and African Americans also sometimes held various jobs as woodcutters, teamsters, clearners, and finishing the cast products.

Admission to the Hopewell Furnace is free. Information and a map of the site can be found at the Visitor Center. This place only gets about 50,000 visitors a year, but it is well worth the time to check out. We were only there a couple of hours but felt like we had plenty of time to enjoy learning about iron production during this time in our country's history.

Website: www.nps.gov.hofu

No comments:

Post a Comment